When World War I broke out in the summer of 1914, Lenin was in Poland. He received the news that the German Socialists had declared their support for the war in the German parliament. That moment was deeply shocking for him, because it meant that the war could no longer be stopped and that the working class would turn into “cannon fodder” — something Lenin and other anti-war socialists had long warned about. Consequently, he had to flee from Poland, which was about to become a battlefield, to Switzerland.

At that time, Lenin decided to do what might seem like the most logical thing he could do under those circumstances — and what was that? Exactly: he went back to reading and studying Hegel’s Logic. It was a strange decision, one that could reflect either deep despair or profound doubt — the kind of doubt that drives one to reexamine the origins of things and the beginnings of creation itself. Yet it was also a logical decision: dark days can at least be useful for reloading one’s intellectual ammunition, preparing one’s thought for a new moment of practice.

Lenin’s reading of Hegel’s Logic was, of course, important. Until that moment, Lenin’s understanding of Marxism had been primarily materialist, and his grasp of dialectical logic rather limited. This limitation had appeared clearly in his harsh stance toward Bogdanov and the empirio-criticist group within the Bolshevik Party in 1908 — a group influenced by neo-Kantianism of Ernest Mach, which held that things do not have an objective existence independent of human consciousness. This was the stimulus of his book Materialism and Empirio-criticism, which he wrote in the British Museum Library’s reading room, where Marx long before used to make his readings and studies.

In rediscovering Hegel, Lenin realized that the dialectical method was not merely a formal reflection of material development, but a genuine logic of change inherent in things themselves — a logic of their own internal movement. Hence, the material development of history might not unfold in the way we expect; it could take other shapes through the workings of dialectic. As a result, Lenin began to lean toward a philosophy of praxis — the idea that practice itself reshapes our concepts. Later on, of course, Gramsci and Georg Lukács would be the most important thinkers to build upon these Leninist insights and experiences.

This probably solidified Lenin’s conviction that the revolution in Russia did not have to wait for a bourgeois-democratic phase, but that the socialists could leap over it and seize power themselves to carry out the transitional stage.

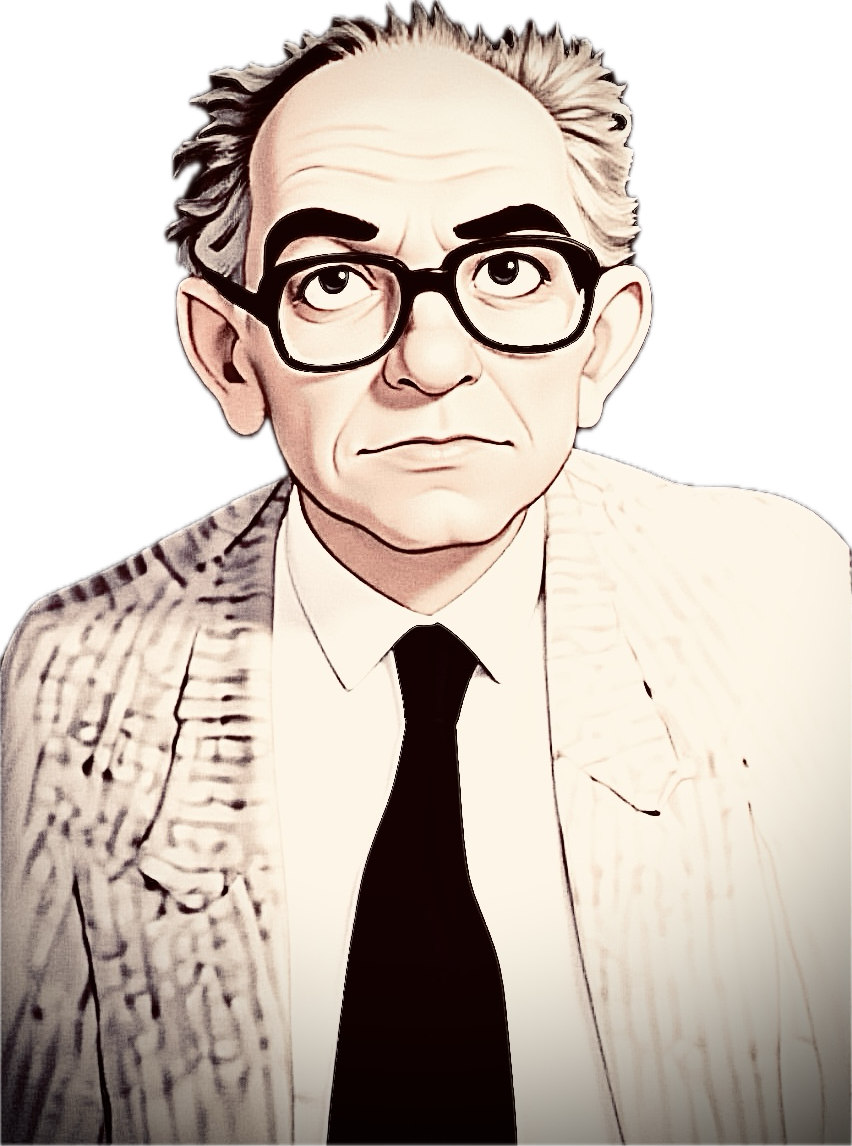

Regardless of how accurate or sound Lenin’s political or philosophical judgment was, one of the most important Arab thinkers influenced by Hegel’s logic and by Lenin’s late reading of it was the late Elias Murqus. Murqus translated Lenin’s Philosophical Notebooks — the very notes Lenin wrote while reading Hegel’s Logic, full of scattered reflections and marginal comments. He wrote extensively on the Hegelian concept of rationality in his Rationalism and Progress and Critique of Arab Rationalism.

Elias Murqus was the one who introduced me to this philosophical background of Lenin on the one hand, and to the modern Hegelian readings on the other — those that view the moment of negation in Hegelian dialectics as a real negation of the thing, not merely a formal one predetermined by the outcome of the dialectical process. In other words, during the dialectical interplay between reality and our ideas about reality, we do not know in advance what the result will be; it’s not that we already have a pre-set conclusion waiting to appear.

Murqus’s ideas here build upon earlier works that had revived the philosophical importance of Hegel — most notably Herbert Marcuse’s doctoral dissertation Hegel’s Ontology and Theory of Historicity, translated into Arabic by the well-known Egyptian Marxist thinker Ibrahim Fathi, and Marcuse’s second book on Hegel, Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory translated by the eminent Egyptian philosopher Fouad Zakariya.

I remembered Murqus — and how little recognition he received — a few days ago while attending a seminar on Hegel at the Center for Contemporary Critical Thought at Columbia University. I watched how the students and professors were interested in Lenin’s reading of Hegel, and exploring the possibility of reading Hegel in a critical, non-dogmatic way. And I couldn’t help but recall how figures like Murqus and other Arab scholars have been unfairly neglected because of the global academic lack of attention toward modern Arab thought — and the continuing lack of English translations of their work to this day.

Back to the beginning, when you face hard times, do not despair. It may be those very hard times that give you the chance to refresh your mind for a new start. If you read Hegel in peace, you could find him too abstract or even boring. Hard times, in contrast, could help you make sense of the abstract, concretize your thought, and end up with novel creative thoughts.